by Pieter Van Bogaert, 2020

Antwerp / Brussels, 28 April, 2 P.M.

Correspondences with Eva van Tongeren

It could have been coffee, but Skype it was. It could have been together at a table, but each at our own table it was. We could have looked each other in the eye, but we make do with our webcams and screens. That’s our comfort. A meeting like many others.

“How are you?”

“What are you doing?”

She talks about the film with the women in Agadez. She is busy making arrangements with Nigerese filmmakers about working together remotely. That sounds familiar. It is in keeping with her earlier works, which I watched over the past few days on the very same screen we are now watching each other on.

(The sound of the sea, the image of the beach and then, barely audible, your breathing in and out at the beginning of your first film and thus of your collected works.)

She talks about the whale cemetery in Antwerp, which presented itself along the way for yet another film. About fossilised whale remains, found where the sea used to be. About urban legends of Antwerp giants dating back to the Middle Ages, when the first whale bones were found in the city. That too sounds familiar: her fascination for whales that links her first with her most recent works. That’s what we talk about when meeting on her and my computer.

(A day earlier, I read a piece by Achille Mbembe about humanity being threatened by suffocation. About the universal right to breathe, about recovering the world’s lungs, the need for a radical break, for radical imagination. I e-mail you the text.)

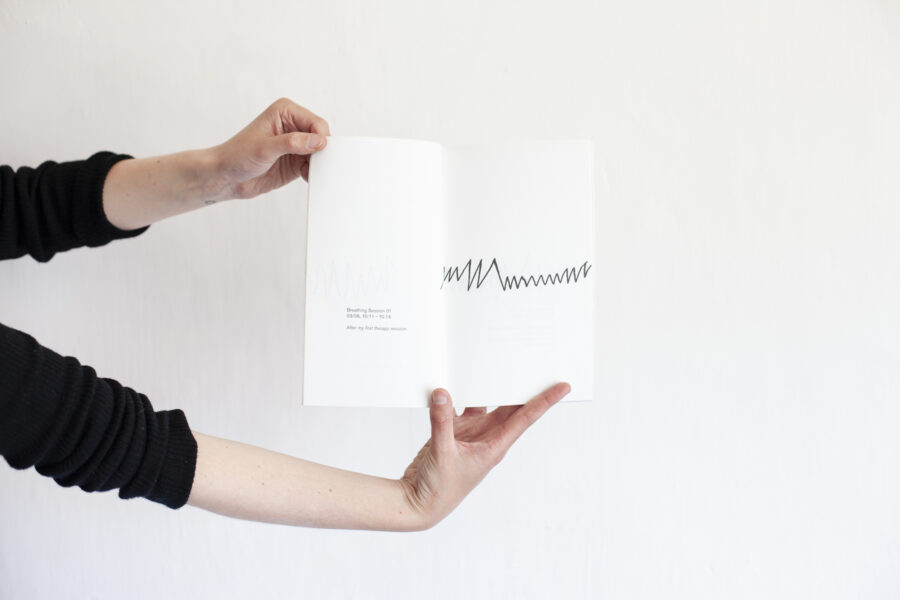

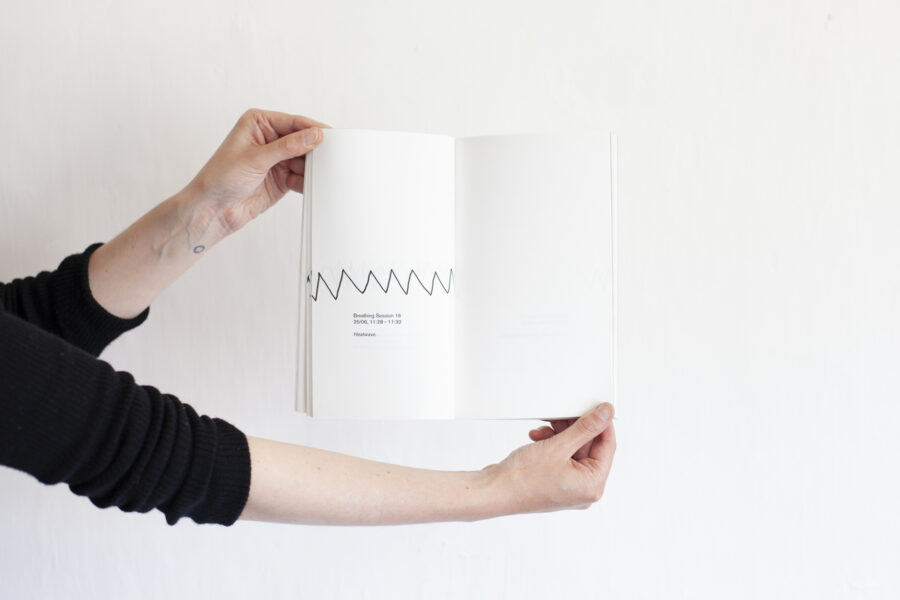

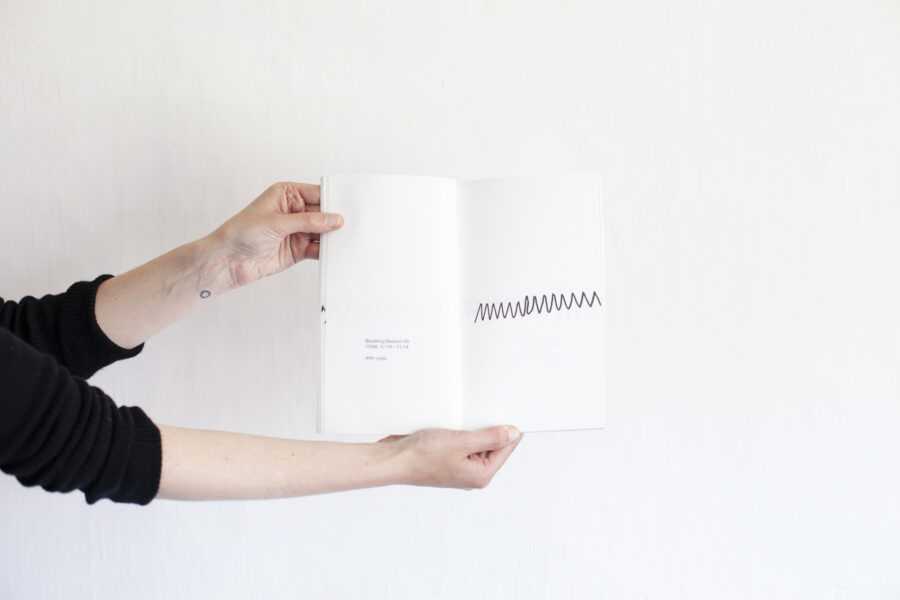

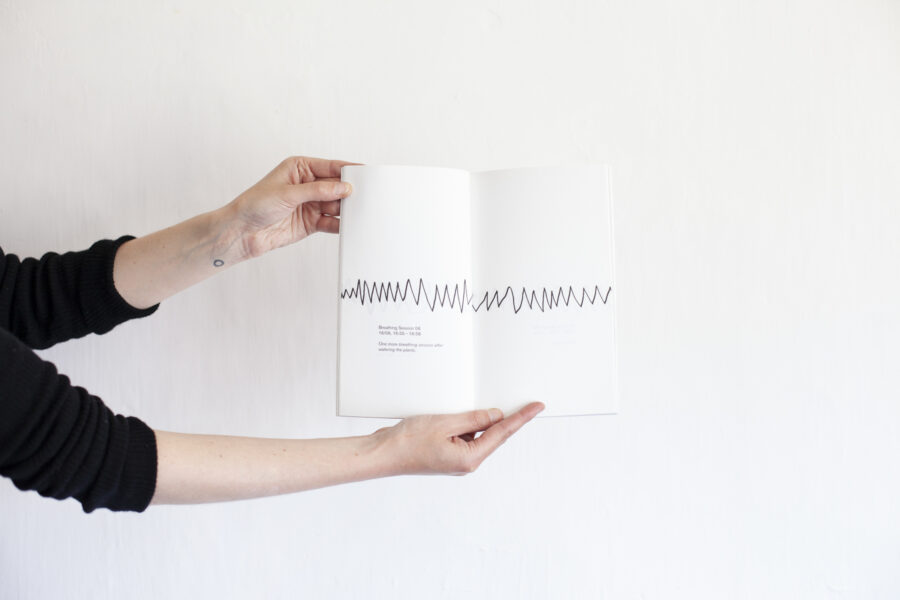

We talk about what takes place out of the picture; about what takes place on-screen and what is suggested outside of it. I call it the space for imagination (and at the very end of the conversation, in the space that is in fact already beyond the scope of the conversation, she will ask if she should add that her films are intended to provoke the imagination? That won’t be necessary.) There is a discrepancy, a contrast, an asynchrony between her images and her stories. The empty streets, houses, gardens in France and her memory of all those people around Evgenia (in There Are No Whales in France, 2015). The images of nature and of her journey through her correspondence with Thomas (in Still from Afar, 2018). The graphs then and the actual breathing now (in Breathing Sessions 1-19, 2019). The fragments of dream analyses accompanying images of a whale safari: the promise of what does not appear, differently (in Fragments of a Dream Analysis, 2019).

You talk about that boat, where everyone is concerned with the image, waiting for the moment of the whale, which mainly moves under the surface: intangible, unreachable, invisible. Out of the picture. You say that everyone on that boat lives on their own island. That those islands sometimes touch. Like the different languages and colours of the subtitles. They too run on and with each other.

It gets more personal. Naturally. That by looking at the other, you want to get to know yourself. That you use film as a pretext for not looking at yourself. (That it is a way to put yourself out of the picture.) I feel the same when I watch your films: a desire to become part of what’s off screen. To be a part of that(wherever that may be). (And also when Skyping, I want to know what your eyes are looking for off screen, what your hands are doing outside the frame.) The importance of the outside for letter writers, prisoners, patients, spectators, therapists: all the correspondences that are so important in your work. Not just the letters in your first films, but more broadly the relationships and ties with the therapist, the self. The dialogue: as personal and as collective analysis. You perform this shift from the personal to the collective masterfully in your latest film, by using your dialogue as subtitles to the multilingual conversations of the other passengers on the boat.

You use the word “image economy”. I think: the economic way in which you use images in your films. Never too much. Always leaving room for the imagination (the space to belong). You mean: a system of exchange. An exchange of images. That is of course what you’re doing in each of your films. That is what you intend to further refine in your work with the women of Agadez and the Nigerese filmmakers who will deliver the images for your next film. You want to make time and space in order to find each other. (Which for you means: the space to belong.) You want to develop a horizontal approach in which the different voices—you, the filmmakers, the women—are given equal attention. You put yourself as a filmmaker in a vulnerable position in which you don’t know or see everything.

As you indeed do not know or see everything. You prefer to find your way in details. You find your subject in a footnote about the women of Agadez who pay their last respects to the bodies of migrants in the Sahel. That footnote touches you, like a piece of humanity in an otherwise technical report of the Clingendael Institute. You’re intrigued. You want to know more about the women in that footnote. You come up with a way to work with them. An image economy.

You want an image of the women’s journey. You let the women inspire you, you take their search as your filming guide. Their care for others, for the sick and the dead; your film is a tribute to the work and the people you portray.

Care. That sounds familiar too. Her thoughts as a European, as a filmmaker, about the refugees on TV in their barques on the sea (in There Are No Whales in France). Her interest in Thomas in prison (in Still from Afar). The care for and about the self (in Breathing Sessions 1-19). Her relation to the therapist and the other people in the boat (in Fragments of a Dream Analysis). And also: her work as a curator for Visite, the film festival she has been organising in Antwerp for the last few years.

You recount. About your desire to show films that would otherwise only reach the festival circuit. How you, as a filmmaker, are curious about the filmmakers behind other films. How important you think it is to introduce filmmakers to your audience. The dialogue. That the making—the taking care of—a programme resembles the editing of a film. You talk through the work of others. You feel like a listener to others’ stories in your own films and the stories in others’ films. You care for your own practice, nourished by those others; you as a hostess during Visite; the importance of meals, of being together, for every screening; the conversations before and after the film; the people who get to know each other there and keep returning for each other, for the films, for the festival: it creates a form of listening that provides you with more freedom, far greater than any speaking or writing.

it is something that has been bothering me lately: how cinephilia today actually works. As a cinephile myself, I always felt that I came after something. That the heyday of cinephilia was over. The heyday, I thought, were the sixties and seventies of the past century, when French critics began making their own films as well as showing those of their contemporaries from other continents or filmmakers from other times. But what about today? Half a century after the fact? Cinephilia today—I feel—is a return to being together: watching films together, sharing, discussing, exchanging. It’s part of a living culture again, even though that culture often looks back upon historical cinephilia, giving it a new relevance. I do not only notice this in Visite, but also in the filmmakers, critics, and curators of Courtisane or Sabzian, who still—or again—discover cinema as genuine amateurs.

She doesn’t like the word “cinephile”. For her, it is linked to a weighty theoretical framework. Visite is about the love of film, of other filmmakers, of watching film together.

For you, making films happens at an unconscious level. Something grows, and that’s what you want to tell. There’s an urgency about the process. Each new subject is a pretext for creating. Which is less the case with showing films. The desire to watch films together is more rational.

Sometimes it feels as if she’s not a filmmaker yet because she never decided to become one. As if she ends up in it, like an amateur. In fact, she says, she feels more like a sculptor, or a weaver, kneading ideas like clay or weaving them like threads. Adding some, removing some, modelling, finding a way for the material. Films? They grow throughout a process, such as her residency at AAIR. She seizes the opportunity to think about form. She would like to get out of cinema, out of that beginning-and-end structure. To search for a fresh contact with her audience. She goes to the museum: a place she likes to visit, where she finds peace. She leaves her comfort zone: cinema, her generous medium, with lots of space and attention for and from the spectator. She wants to evoke that same generosity by means of an installation. She creates Breathing Sessions 1-19 and places the work in a black hole at the top of the stairs at Extra City. Four beanbags with as many sets of headphones complete the isolation. The vibrating woofer turns it into a physical experience. Breathing Sessions 1-19 is an exercise in empathy (belonging?). In herself: at the request of a therapist she does breathing sessions whilst drawing her breathing. By hand. This is about what she feels; she’s not a machine. Her hand makes itself felt in the graphs, especially when the (exhaling) downward line bears off to the left (thus going back in time). She searches for the tension between the organic and the mechanical. She makes the immeasurable tangible. It’s not the woofer that renders it physical, but the moment the spectator decides to breathe along. I am not alone. Merely looking and listening is too abstract. Her breathing makes me dizzy. It’s uncanny. Unpleasant. Intimate and subjective. Successful. Her place becomes my place. Her experience becomes my empathy. Concerns are shared.

In Extra City, you also show an installation version of Fragments of a Dream Analysis, originally a film with a beginning and an end. (You did the same with Still from Afar during the Videonale in Bonn, and you were worried that not everyone would have the full film experience. There is no full experience of Breathing Sessions 1-19, only yours and mine. Which is the very meaning of the title’s 1-19: they’re mere fragments, a selection. You get in and you get out.) You take me along in that boat where everyone is filming. Everyone is sharing the same experience. Everyone indiscreet. It puts you at ease. You disappear among the other filmers, viewers, voyeurs. All those people, together, side by side. All those different languages, subtitled with fragments from your dream analysis. Different analyses in different colours become a collective analysis. Everyone is pursuing the same dream. Everyone in the same boat, on the same safari. A whale safari, looking for that beast beneath the surface: big, mystical, intense, tender, modest, exciting, reassuring. That mammal surviving in the sea, the place where you can’t breathe. World-encompassing freedom. The dream, the desire (is it a he or a she? Eva?). You are the whale. The boy you are following in the most beautiful images of your film, willingly and uncomfortably in his father’s arms, making way for the smaller boy, dozing off on a bench: he is the whale. (Is he following you? Or are you following him? And is it true that it is mainly male scientists who look for and find Freudian interpretations in the desire for whales? The American neuroscientist, psychoanalyst and philosopher John C. Lily, whose flaccid penis, which was presented to him in a dream, resembles the dolphins he communicates with on a daily basis; Jonas travelling in the whale’s womb-like belly; the gay eroticism in Melville’s Moby Dick.) All those different realities, exchanged glances, dreams, and desires are part of the collective therapy.

People sometimes ask: is it real?

Truth, for you, is self-evident. Only by telling it again does it become fiction. You love that. The freedom of translating. Until you no longer know where you start talking and stop listening. Evgenia’s letter, read by your voice? The barque full of refugees as a TV image or the continuation of their journey as a film-to-be-made? Those lines breathing back in time? Safaris as an authentic experience? Fiction or reality? You indicate the time, as proof: July 30, 10 A.M. But what happens on that 30th of July? (Which 30th of July?) The journey? The analysis? (Which analysis?) In Breathing Sessions 1-19, each session represents a specific moment. Time is something to hold on to here. Whilst your first films are more about duration. About slowness, of the journey, of the images. Your time is an invitation to the here and now, even if it’s a construction: it’s the only time that counts. Is that why you switch languages in your films? Why you switch voices? Your language and voice in your first films as a direct way of addressing. The ambiguity of different languages and voices in your latest film as a consciousness-expanding question: “Who is speaking?” (You, of course. But never without entering into others. Never without your subject and never without your audience as a pretext for that film that keeps insisting. That personal signature marks your nascent oeuvre.)

You know, Eva? I would have liked to write you a letter. But that would have been too literal. I’d hardly know how to address you. I still have to find my own style as your audience. To follow the circumstances and belong that way. But if I would write a letter after all—after all those films in which you share your care for and your concern about yourself and others—I would open with a sincere “How are you?” Eva?